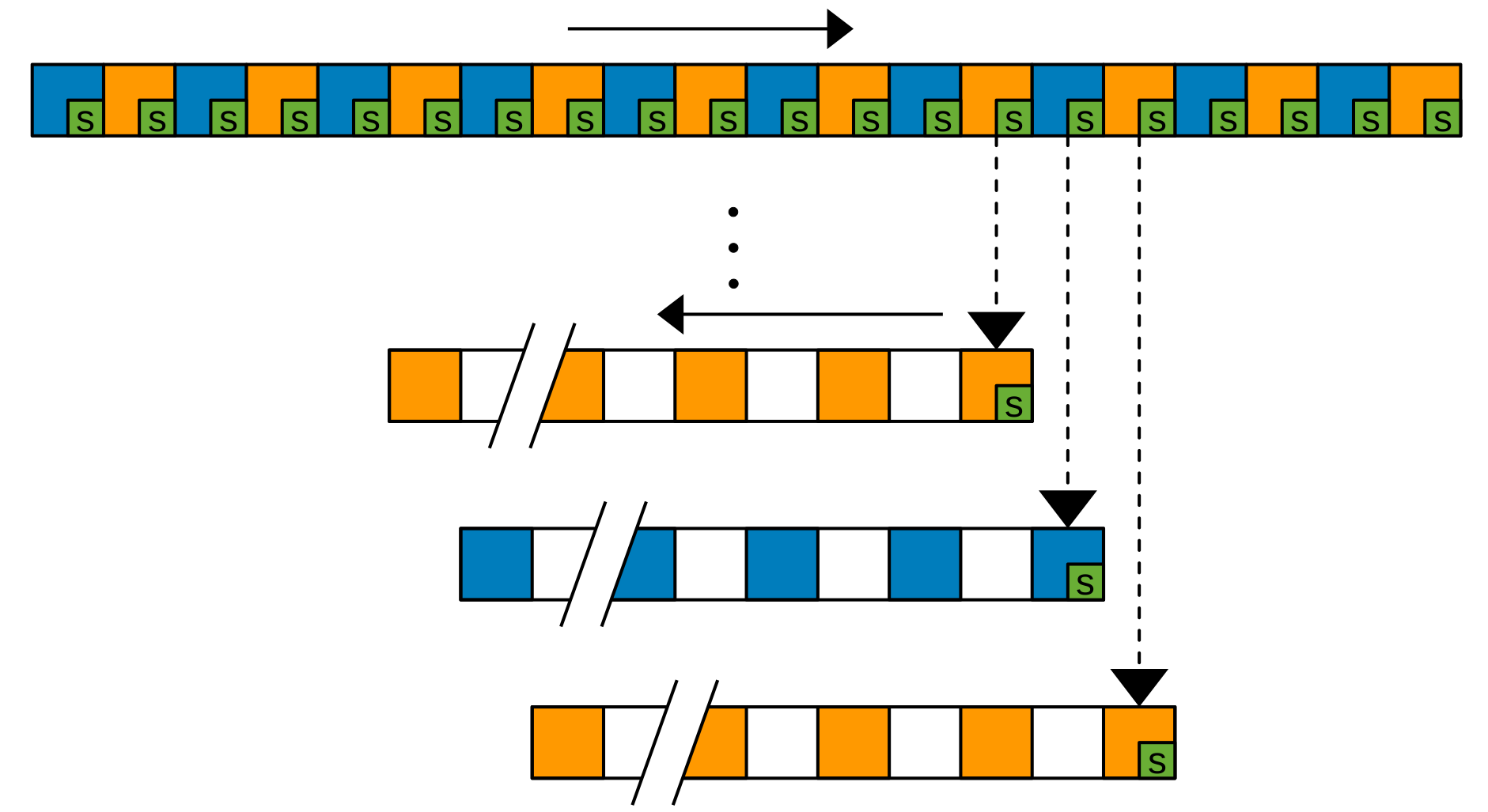

We demonstrate Deep Redundancy (DRED) for the Opus codec. DRED makes it possible to include up to 1 second of redundancy in every 20-ms packet we send. That will make it possible to keep a conversation even in extremely bad network conditions.

We demonstrate Deep Redundancy (DRED) for the Opus codec. DRED makes it possible to include up to 1 second of redundancy in every 20-ms packet we send. That will make it possible to keep a conversation even in extremely bad network conditions.

Note: This is a first-person account of my involvement in Opus. Since I was not part of the early SILK efforts mentioned below, I cannot speak about its early development. That part is omitted from this account but by no means is that intended to diminish its importance to Opus.

Opus is an open-source, royalty-free, highly versatile audio codec standard. It is now deployed in billions of devices. This is how it came to be. Even before Opus, I had a strong interest in open standards, which led me to start the Speex project in 2002, with help from David Rowe. Speex was one of the first modern royalty-free speech codecs. It was shipped in many applications, especially games, but because it was slightly inferior to the standard codecs of the time, it never achieved a critical mass of deployment.

In 2007, when working on a high-quality videoconferencing project as part of my post-doc, I realized the need for a high-fidelity audio codec that also had very low delay suitable for interactive, real-time applications. At the time, audio codecs were mostly divided into two categories: there were high-delay, high-fidelity transform codecs (like MP3, AAC, and Vorbis) that were unsuitable for real-time operation, and there were low-delay speech codecs (like AMR, Speex, and G.729) with limited audio quality.

That is why I started the Opus ancestor called CELT, an effort to create a high-fidelity transform codec with an ultra low delay around 4-8 ms — even lower than the 20 ms typical delay for VoIP and videoconferencing. My first step was to discuss with Christopher "Monty" Montgomery, who had previously designed Ogg Vorbis, a high-delay, high-fidelity codec, and was then looking at designing a successor. Even though our sets of goals proved too different for us to merge the two efforts, the discussion was very helpful in that I was able to gain some of the experience Monty got while designing Vorbis. The most important advice I got was "always make sure the shape of the energy spectrum is preserved". In Vorbis (and other codecs), that energy constraint was only partially achieved, through very careful tuning of the encoder, and sometimes at great cost in bitrate. For CELT, I attacked the problem from a different perspective: What if CELT could be designed so that the constraint was built into the format, and thus mathematically impossible to violate?

This is where the CELT name originated: Constrained Energy Lapped Transform. The format itself would constrain the energy so that no effort or bits would be wasted. Although simple in principle, that idea required completely new compression and math techniques that had never previously been used in transform codecs. One of them was algebraic vector quantization, which had been used for a long time in speech codecs, but never in transform codecs, which still used scalar quantization. Overall, it took about 2 years to figure out the core of the CELT technology, with the help of Tim Terriberry, Greg Maxwell, and other Xiph contributors.

Because of the ultra low delay constraint, CELT was not trying to match or exceed the bitrate efficiency of MP3 and AAC, since these codecs benefited from a long delay (100-200 ms). It was thus a complete surprise when — only 6 months after the first commits — a listening test showed CELT already out-performing MP3 despite the difference in delay. That was attributed to the ancient technology behind MP3. CELT was still behind the more recent AAC, with no plan to compete on efficiency alone.

Despite still being in early development, some people started using CELT for their projects, mostly because it was the only codec that would suit their needs. These early users greatly helped CELT to improve by providing real-life use cases and raising issues that could not have been foreseen with just "lab" testing. For example, a developer who was using CELT for network music performances (musicians playing live together in different cities) once complained that "CELT works very well for everyone, except for me with my bass guitar". By getting an actual sample, it was easy to find the problem and address it. There were many similar stories and over a few years, many parts of CELT were changed or completely rewritten.

There has been no mention of the name Opus so far because there was still a missing piece. Around the same time CELT was getting started, another codec effort was quietly started by Koen Vos, Søren Skak Jensen, and Karsten Vandborg Sørensen at Skype under the name SILK. SILK was a more traditional speech codec, but with state-of-the-art efficiency, competing with or exceeding other speech codecs. We became aware of SILK in 2009 when Skype proposed it as a royalty-free codec to the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF), the main standards body governing the Internet. We immediately joined the effort, proposing CELT to the emerging working group. It was a highly political effort, given the presence of organizations heavily invested in royalty-bearing codecs. There was thus strong pressure into restricting the working group’s effort to standardizing a single codec. That drove us to investigate ways to combine SILK and CELT. The two codecs were surprisingly complementary, SILK being more efficient at coding speech up to 8 kHz, and CELT being more efficient at coding music and achieving delays below 10 ms. The only thing none of the codecs did very efficiently was coding high-quality speech covering the full audio bandwidth (up to 20 kHz). This is where both SILK and CELT could be used simultaneously and achieve high-quality, fullband speech codec at just 32 kb/s, something no other codecs could achieve. Opus was born and, thanks to the IETF collaboration, the result would be better than the sum of its SILK and CELT parts.

Integrating SILK and CELT required changes to both technologies. On the CELT side, it meant supporting and optimizing for frame sizes up to 20 ms — no longer ultra-low delay but low enough for videoconferencing. Through collaboration in the working group, CELT also gained a perceptual pitch post-filter contributed by Raymond Chen at Broadcom. The post-filter and the 20-ms frames also increased the efficiency to the point where some audio enthusiasts started comparing Opus to HE-AAC on music compression. Unsurprisingly, they found the higher-delay HE-AAC to have higher quality at the same bitrate, but they also started providing specific feedback that helped improve Opus. This went on for several months, until a listening test eventually showed Opus having higher quality than HE-AAC, despite HE-AAC being designed for much higher delays. At that point, Opus really became a universal audio codec. It was either on par or better than all other audio codecs, regardless of the application, be it speech, music, real-time, storage, or streaming.

Opus officially became an IETF standard in 2012. At the time, the IETF was also defining the WebRTC standard for videoconferencing on the web. Thanks to its efficiency and its royalty-free nature, Opus became the mandatory-to-implement standard for WebRTC. In part thanks to WebRTC, Opus is now included in all major browsers and in both the Android and iOS mobile operating systems. It is also used alongside AV1 in YouTube. Most large technology companies now ship products using Opus. This ensures inter-operability across different applications that can communicate with a common codec. Because there are no royalties, it also enables some products that would not otherwise be viable (e.g. because you can't afford to pay a 0.50$ royalty for each freely-downloaded copy of a client software).

As for many other codecs, only the Opus decoder is standardized, which means that the encoder can keep improving without breaking compatibility. This is how Opus keeps improving to this day, with the latest version, Opus 1.3, released in October 2018.

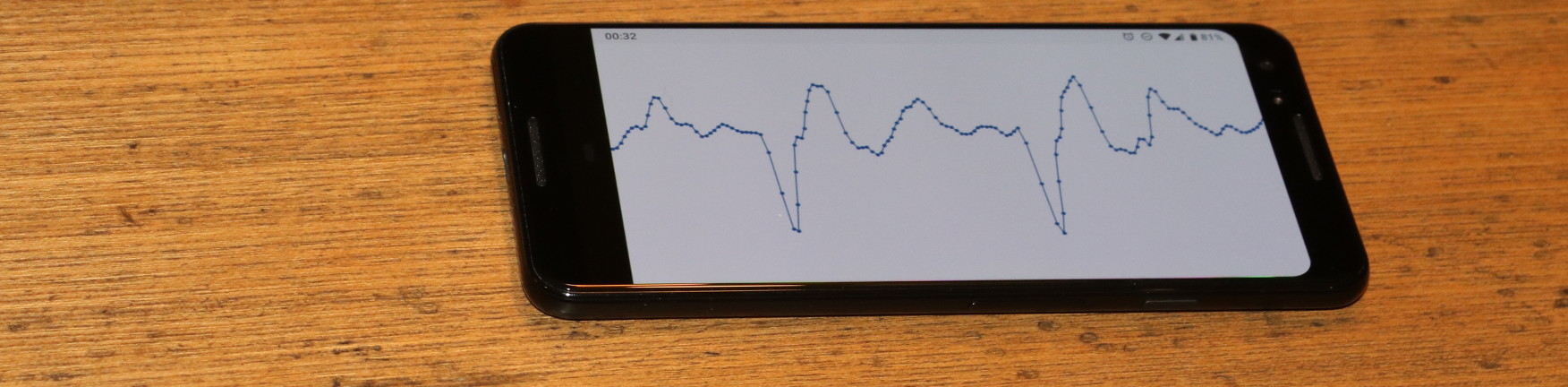

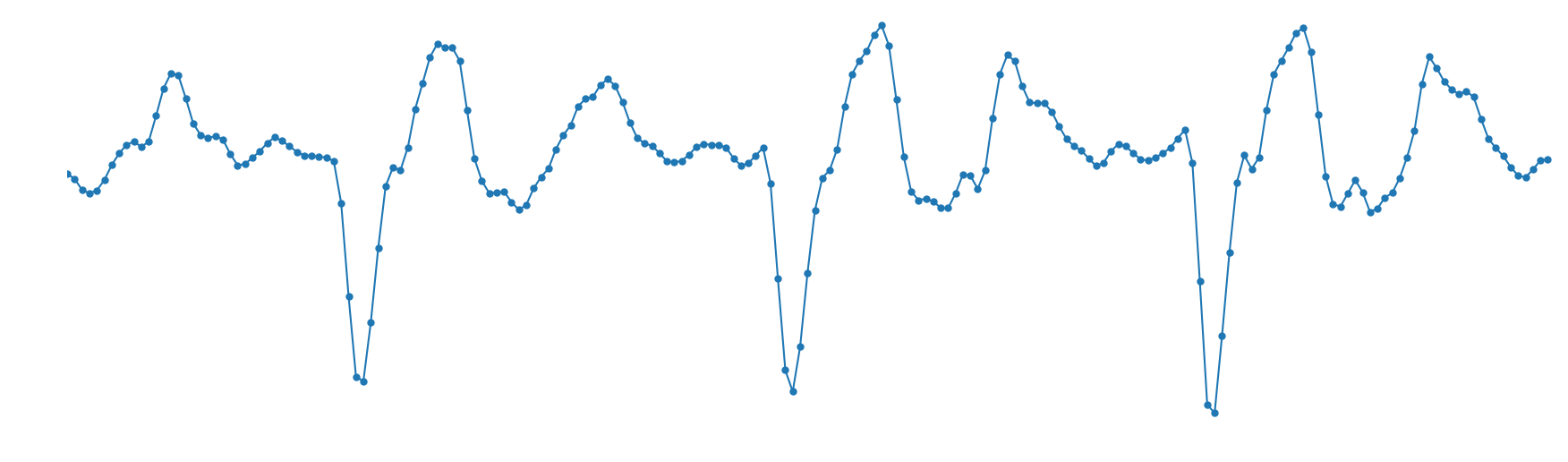

This is a follow-up on the first LPCNet demo. In this new demo, we turn LPCNet into a very low-bitrate neural speech codec (see submitted paper) that's actually usable on current hardware and even on phones. It's the first time a neural vocoder is able to run in real-time using just one CPU core on a phone (as opposed to a high-end GPU). The resulting bitrate — just 1.6 kb/s — is about 10 times less than what wideband codecs typically use. The quality is much better than existing very low bitrate vocoders and comparable to that of more traditional codecs using a higher bitrate.

This new demo presents LPCNet, an architecture that combines signal processing and deep learning to improve the efficiency of neural speech synthesis. Neural speech synthesis models like WaveNet have recently demonstrated impressive speech synthesis quality. Unfortunately, their computational complexity has made them hard to use in real-time, especially on phones. As was the case in the RNNoise project, one solution is to use a combination of deep learning and digital signal processing (DSP) techniques. This demo explains the motivations for LPCNet, shows what it can achieve, and explores its possible applications.

Opus gets another major update with the release of version 1.3. This release brings quality improvements to both speech and music, while remaining fully compatible with RFC 6716. This is also the first release with Ambisonics support. This Opus 1.3 demo describes a few of the upgrades that users and implementers will care about the most. You can download the new version from the Opus website.

Opus gets another major update with the release of version 1.3. This release brings quality improvements to both speech and music, while remaining fully compatible with RFC 6716. This is also the first release with Ambisonics support. This Opus 1.3 demo describes a few of the upgrades that users and implementers will care about the most. You can download the new version from the Opus website.

This demo presents the RNNoise project, showing how deep learning can be applied to noise suppression. The main idea is to combine classic signal processing with deep learning to create a real-time noise suppression algorithm that's small and fast. No expensive GPUs required — it runs easily on a Raspberry Pi. The result is much simpler (easier to tune) and sounds better than traditional noise suppression systems (been there!).

Over the last three years, we have published a number of Daala technology demos. With pieces of Daala being contributed to the Alliance for Open Media's AV1 video codec, now seems like a good time to go back over the demos and see what worked, what didn't, and what changed compared to the description we made in the demos.

Here's the latest addition to the Daala demo series. This demo describes the new Daala deringing filter that replaces a previous attempt with a less complex algorithm that performs much better. Those who like the know all the math details can also check out the full paper.

Here's my new contribution to the Daala demo effort. Perceptual Vector Quantization has been one of the core ideas in Daala, so it was time for me to explain how it works. The details involve lots of maths, but hopefully this demo will make the general idea clear enough. I promise that the equations in the top banner are the only ones you will see!

As a contribution to Monty's Daala demo effort, I decided to demonstrate a technique I've recently been developing for Daala: image painting. The idea is to represent images as directions and 1-D patterns.

Three years ago Opus got rated higher than HE-AAC and Vorbis in a 64 kb/s listening test. Now, the results of the recent 96 kb/s listening test are in and Opus got the best ratings, ahead of AAC-LC and Vorbis. Also interesting, Opus at 96 kb/s sounded better than MP3 at 128 kb/s.

I just got back from the 135th AES convention, where Koen Vos and I presented two papers on voice and music coding in Opus.

Also of interest at the convention was the Fraunhofer codec booth. It appears that Opus is now causing them some concerns, which is a good sign. And while we're on that topic, the answer is yes :-)

Ever since we started working on Opus at the IETF, it's been a recurring theme. "You guys don't know how to test codecs", "You can't be serious unless you spend $100,000 testing your codec with several independent labs", or even "designing codecs is easy, it's testing that's hard". OK, subjective testing is indeed important. After all, that's the main thing that differentiates serious signal processing work from idiots using $1000 directional, oxygen-free speaker cable. However, just like speaker cables, more expensive listening tests do not necessarily mean more useful results. In this post I'm going to explain why this kind of thinking is wrong. I will avoid naming anyone here because I want to attack the myth of the $100,000 listening test, not the people who believe in it.

Back in the 70s and 80s, digital audio equipment was very expensive, complicated to deploy, and difficult to test at all. Not everyone could afford analog-to-digital converters (ADC) or digital-to-analog converters (DAC), so any testing required using expensive, specialized labs. When someone came up with a new piece of equipment or a codec, it could end up being deployed for several decades, so it made sense to give it to one of these labs to test the hell out of it. At the same time, it wasn't too hard to do a good job in testing because algorithms were generally simple and codecs only supported one or two modes of operation. For example, a codec like G.711 only has a single bit-rate and can be implemented in less than 10 lines of code. With something that simple, it's generally not too hard to have 100% code coverage and make sure all corner cases are handled correctly. Considering the investments involved, it just made sense to pay tens or hundreds of thousands of dollars to make sure nothing blows up. This was paid by large telcos and their suppliers, so they could afford it anyway.

Things remained pretty much the same through the 90s. When G.729 was standardized in 1995, it still only had a single bit-rate, and the computational complexity was still beyond what a PC could do in real-time. A few years later, we finally got codecs like AMR-NB that supported several bit-rates, though the number was still small enough that you could test each of them.

When we first attempted to create a codec working group (WG) at the IETF, some folks were less than thrilled to have their "codec monopoly" challenged. The first objection we heard was "you're not competent enough to write a codec". After pointing out that we already had three candidate codecs on the table (SILK, CELT, BroadVoice), created by the authors of 3 already-deployed codecs (iSAC, Speex, G.728), the objection quickly switched to testing. After all, how was the IETF going to review this work and make sure it was any good?

The best answer came from an old-time ("gray beard") IETF participant and was along the lines of: "we at the IETF are used to reviewing things that are a lot harder to evaluate, like crypto standards. When it comes to audio, at least all of us have two ears". And it makes sense. Among all the things the IETF does (transport protocols, security, signalling, ...), codecs are among the easiest to test because at least you know the criteria and they're directly measurable. Audio quality is a hell of a lot easier to measure than "is this cipher breakable?", "is this signalling extensible enough?", or "Will this BGP update break the Internet?"

Of course, that was not the end of the testing story. For many months in 2011 we were again faced with never-ending complaints that Opus "had not been tested". There was this implicit assumption that testing the final codec improves the codec. Yeah right! Apparently, the Big-Test-At-The-End is meant to ensure that the codec is good and if it's not then you have to go back to the drawing board. Interestingly, I'm not aware of a single ITU-T codec for which that happened. On the other hand, I am aware of at least one case where the Big-Test-At-The-End revealed someting wrong. Let's look at the listening test results from the AMR-WB (a.k.a. G.722.2) codec. AMR-WB has 9 bitrates, ranging from 6.6 kb/s to 23.85 kb/s. The interesting thing with the results is that when looking at the two highest rates (23.05 and 23.85) one notices that the 23.85 kb/s mode actually has lower quality than the lower 23.05 bitrate. That's a sign that something's gone wrong somewhere. I'm not aware of why that was the case or what exactly happened from there, but apparently it didn't bother people enough to actually fix the problem. That's the problem with final tests, they're final.

What I've learned from Opus is that it's possible to have tests that are far more useful and much cheaper. First, final tests aren't that useful. Although we did conduct some of those, ultimately their main use ends up being for marketing and bragging rights. After all, if you still need these tests to convince yourself that your codec is any good, something's very wrong with your development process. Besides, when you look at a codec like Opus, you have about 1200 possible bitrates, using three different coding modes, four different frame sizes, and either mono or stereo input. That's far more than one can reliably test with traditional subjective listening tests. Even if you could, modern codecs are complex enough that some problems may only occur with very specific audio signals.

The single testing approach that gave us the most useful results was also the simplest: just put the code out there so people can use it. That's how we got reports like "it works well overall, but not on this rare piece of post-neo-modern folk metal" or "it worked for all our instruments except my bass". This is not something you can catch with ITU-style testing. It's one of the most fundamental principles of open-source development: "given enough eyeballs, all bugs are shallow". Another approach was simply to throw tons of audio at it and evaluate the quality using PEAQ-style objective measurement tools. While these tools are generally unreliable for precise evaluation of a codec quality, they're pretty good at flagging files the codec does badly on for further analysis.

We ended up using more than a dozen different approaches to testing, including various flavours of fuzzing. In the end, when it comes to the final testing, nothing beats having the thing out there. After all, as our Skype friends would put it:

Which codec do you trust more? The codec that's been tested by dozens of listeners in a highly controlled lab, or the codec that's been tested by hundreds of millions of listeners in just about all conditions imaginable?It's not like we actually invented anything here either. Software testing has evolved quite a bit since the 80s and we've mainly attempted to follow the best practices rather than use antiquated methods "because that's what we've always done".

We just released Opus 1.1-alpha, which includes more than one year of development compared to the 1.0.x branch. There are quality improvements, optimizations, bug fixes, as well as an experimental speech/music detector for mode decisions. That being said, it's still an alpha release, which means it can also do stupid things sometimes. If you come across any of those, please let us know so we can fix it. You can send an email to the mailing list, or join us on IRC in #opus on irc.freenode.net. The main reason for releasing this alpha is to get feedback about what works and what does not.

Most of the quality improvements come from the unconstrained variable bitrate (VBR). In the 1.0.x encoder VBR always attempts to meet its target bitrate. The new VBR code is free to deviate from its target depending on how difficult the file is to encode. In addition to boosting the rate of transients like 1.0.x goes, the new encoder also boosts the rate of tonal signals which are harder to code for Opus. On the other hand, for signals with a narrow stereo image, Opus can reduce the bitrate. What this means in the end is that some files may significantly deviate from the target. For example, someone encoding his music collection at 64 kb/s (nominal) may find that some files end up using as low as 48 kb/s, while others may use up to about 96 kb/s. However, for a large enough collection, the average should be fairly close to the target.

There are a few more ways in which the alpha improves quality. The dynamic allocation code was improved and made more aggressive, the transient detector was once again rewritten, and so was the tf analysis code. A simple thing that improves quality of some files is the new DC rejection (3-Hz high-pass) filter. DC is not supposed to be present in audio signals, but it sometimes is and harms quality. At last, there are many minor improvements for speech quality (both on the SILK side and on the CELT side), including changes to the pitch estimator.

Another big feature is automatic detection of speech and music. This is useful for selecting the optimal encoding mode between SILK-only/hybrid and CELT-only. Unlike what some people think, it's not as simple as encoding all music with CELT and all speech with SILK. It also depends on the bitrate (at very low rate, we'll use SILK for music and at high rate, we'll use CELT for speech). Automatic detection isn't easy, but doing so in real-time (with no look-ahead) is even harder. Because of that the detector tends to take 1-2 seconds before reacting to transitions and will sometimes make bad decisions. We'd be interested in knowing about any screw ups of the algorithm.

The new encoder can also detect the bandwidth of the input signal. This is useful to avoid wasting bits encoding frequencies that aren't present in the signal. While easier than speech/music detection, bandwidth detection isn't as easy as it sounds because of aliasing, quantization and dithering. The current algorithm should do a reasonable job, but again we'd be interested in knowing about any failure.